The Paradox

Working in frontier tech, I'm astounded every day by the technology I encounter and how it's progressed us. If you were born in 1000 AD, your living standards were about the same as a peasant in 1700, because the level of technology was functionally the same. Technological progress is the only long-term driver of prosperity.

Today we live with instant global communication, vast computational power in every pocket, medical miracles that extend life. And yet 73% expect inequality to worsen, and more people expect average living standards to worsen (44%) than improve (20%) by 2050. 58% of Americans say life today is worse than 50 years ago for "people like them."

I've been trying to understand this disconnect and there's a framework from Epicurus that keeps coming back to me. He distinguished between three types of desires: natural and necessary (friendship, freedom from pain, basic shelter), natural but unnecessary (luxury, variety, fancy pleasures), and vain and empty (wealth, fame, power). He argued a good life comes from satisfying the first while being moderate about the second and largely ignoring the third.

For most of technological history, arguably, this is exactly what progress delivered. The spinning jenny freed people from backbreaking labour. Vaccines eliminated childhood diseases. The five-day work week gave people time for rest and community. Technology overwhelmingly served those natural and necessary desires, the foundations of a good life.

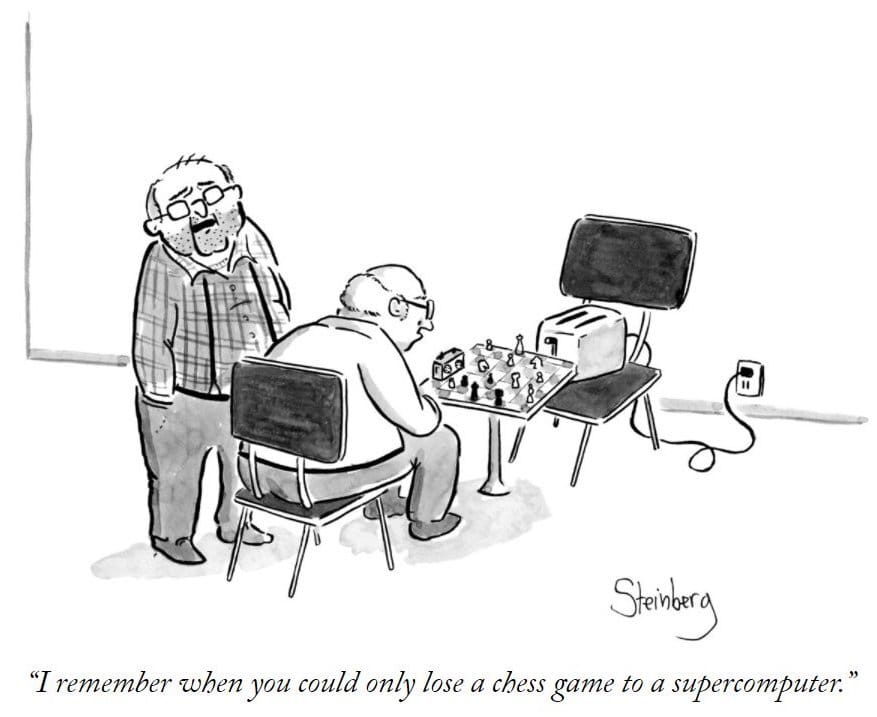

But something shifted in the last 30-40 years. Technology increasingly delivers abundance in the "natural but unnecessary" category (infinite consumer goods, streaming entertainment, next-day delivery of anything imaginable). It enables "vain and empty" pursuits at unprecedented scale: wealth accumulation, status signaling, competitive advantage. Meanwhile, it seems to actively degrade the conditions for a good life as Epicurus defined it: less time for friendship, less autonomy over work, more anxiety, less real community.

AI has amplified and intensified something that was already happening, and hopefully can also serve as a way out. But for now, I want to delve into how tech can feel like decline across work, play and life.

More productivity and more... work?

For most of the 20th century, productivity gains translated into human relief. Workers didn't just earn more; they worked less. The five-day week, paid holidays, shorter workdays were enabled by the economic surplus (and labour movements) that technological progress created. More output per hour meant fewer hours required.

But that promise broke somewhere. Between 1979 and 2025, productivity increased 87.3%. If those gains had translated into leisure the way they had before, we'd be working 30-hour weeks. Instead, the average American worker added 181 hours per year between 1979 and 2007 (equivalent to 4.5 extra weeks).

Productivity gains should have made work either shorter or easier, or both. Instead, work got longer in many cases, and more stressful pretty much universally. What gives?

Well, the nature of work transformed. It bifurcated into two options that are both bad in different ways. At one end you have high-stress knowledge work with good pay but crushing pressure. Long hours despite nominally "40-hour" contracts. Constant availability. By 2024, 82% of knowledge workers reported burnout. Nearly half say they never fully switch off (checking emails at dinner, taking calls on vacation).

At the other end: precarious service work where you're juggling multiple jobs, dealing with unpredictable scheduling, no real progression. To add insult to injury: the bottom 20% of earners saw their annual hours increase 22% between 1979 and 2007, which is far more than higher earners.

The intensification shows up in the data in other, slightly depressing ways. Between the late 1990s and 2017, UK employees working to "tight deadlines" at least three-quarters of the time rose from 53% to 60%. Those working at "very high speed" nearly doubled from 23% to 45%.

The mid-century middle class had something neither end of today's barbell has: reasonable hours, security, autonomy. Enough time for family and community. Stability to plan a life. Work that ended when you left the building. That combination (which delivered on Epicurus's "natural and necessary" desires) has largely vanished even though we produce 2.7 times more per hour than in 1979 - in short, we often have less agency over how, when, or under what conditions that output is generated. The surplus went somewhere; it just didn't buy us relief.

Why the essentials got expensive

There's another dynamic that explains part of this, one that's more directly about how technology works. Consumer goods have gotten spectacularly cheap while the foundations of a good life have become more expensive. TVs, clothes, gadgets: cheaper every year - in fact,a TV that would have cost several thousand dollars in the early 2000s can now be bought for a few hundred dollars. Healthcare, education, childcare: the things you actually need for security and flourishing, are increasingly out of reach.

This is what economists call Baumol's cost disease. In sectors where technology drives productivity gains (manufacturing, agriculture, retail), output per worker soars. A factory worker today makes far more widgets per hour than in 1980, so even with higher wages, each widget costs less. This is why your TV is cheaper.

But healthcare, education, and social care resist automation (or have until now). You still need one teacher per classroom, one nurse per patient, one caregiver per elderly person. Productivity barely grows. Yet wages in these sectors must still rise due to economy-wide labour market competition. When wages rise without corresponding productivity gains, costs per unit must increase. So the price of a doctor's appointment, childcare, or schooling climbs, even though the service delivered is essentially the same as it was decades ago.

The numbers are pretty stark. College tuition increased ~200% since 1963-64 after adjusting for inflation. Childcare costs rose ~214% since 1990 while wages rose just 28%. Healthcare premiums tripled. Housing shows something similar (though for different reasons I'll get into in another piece): in 1970 it took less than three years of median San Francisco income to buy a home; today it's 10x annual income.

So technology fills our increasingly expensive homes with cheap material goods (Epicurus's "natural but unnecessary" pleasures) while the infrastructure for a good life becomes inaccessible. You can afford a new phone every year but not reliable childcare. This is the abundance paradox: drowning in consumer goods while the foundations of security, health, and human development either cost too much or degrade from insufficient funding. Technology's abundance flows to the wrong categories entirely.

When the connections multiply but the friendships disappear

Going back to basics: if relationships are at the very top of "natural and necessary" desires (more important than wealth, status, or luxury), then by this measure, we're failing catastrophically.

In 1990, only 3% of Americans said they had no close friends. By 2021: 12%. The average American sees friends in person 41 days per year, down from 57 days in 2013 and from 70-ish days per year in the 1970s. Sexual intimacy is also plummeting. The share of young men reporting no sexual activity in the past year tripled from 8% in 2008 to 28% by 2018, and the stats are similar for women. A world where everyone meets on dating apps in particular accelerate not just a feeling of disconnect, but actual loneliness for many-internal and third-party analyses suggest strong winner-take-most dynamics—roughly Pareto 80/20 style, where a minority of men receive a majority of likes.

And what replaced real community? Algorithmically optimized dopamine delivery systems. Social media and dating apps exploits variable reward schedules (the uncertainty of whether this scroll will engage, this swipe will match). It's the exact mechanism that makes gambling addictive. Pull-to-refresh, infinite scroll, autoplay aren't bugs; they're features designed to eliminate stopping points and keep you in the dopamine loop.

We're doing this to kids whose brains are still developing. Facebook's internal research showed Instagram was toxic for teenage girls' mental health. In The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt shows compelling data for the jump in teen suicide and eating disorders coinciding specifically when social media proliferated.These effects are showing up academically too: for the first time in modern history, American children are less literate than the generation before. Math scores for 9-year-olds declined for the first time in 2022 (although it should be mentioned the effect of covid pandemic on schooling is a confounding factor here). By 2024, 40% of 4th graders scored below basic reading proficiency. Smartphone ownership among adolescents took off around 2013, exactly when eighth-grade scores peaked before falling.

But there's something else happening here that explains why we're not just lonelier but more polarized. Social contact theory suggests that interpersonal contact under the right conditions (equal status, common goals, cooperation, institutional support) reduces prejudice and builds understanding. Digital interaction strips away all those conditions.

When your "contact" with out-groups happens through algorithmically curated feeds, you're not getting the humanizing effect of real social contact. You see caricatures, the worst examples, rage-bait. No equal status markers, no common goals, no cooperation. The algorithm optimizes for engagement, and outrage is engaging.

So it's not just that we're replacing friendship with dopamine slots. We're replacing the actual social contact that prevents societies from fragmenting into hostile camps. The loneliness epidemic, the mental health crisis among young people, the political polarization- I don't think these are disconnected trends. They're what happens when you strip away social infrastructure and replace it with algorithmically optimized content designed to keep you scrolling.

Technology promised to connect us. Instead it isolated us, destroyed conditions for meaningful friendship, and splinter us into hostile tribes who literally can't see each other as human anymore. By Epicurus's measure (having meaningful relationships, freedom from anxiety, real community), we're poorer than ever, despite being constantly "connected."

Why you can't individually escape

Even if you understand all this, even if you want to reclaim time and community and sanity, you probably can't (not alone). The coordination problem is explained in Yuval Noah Harari's Sapiens, about how the Agricultural Revolution trapped humanity.

Hunter-gatherers actually had it pretty good by most measures. They worked maybe 3-4 hours a day gathering food, had varied diets, plenty of leisure time. Then someone had the clever idea to plant wheat. Seemed reasonable: do a bit of extra work, have a backup food supply.

But here's what happened. Wheat farming produced more calories per acre, which meant more children survived, which meant more mouths to feed, which meant you needed to plant more wheat, which meant clearing more land and working longer hours. And wheat is fragile. It needs constant attention, regular watering, protection from pests and weather. So you're tied to one place, doing repetitive backbreaking labor, eating a less varied diet than your ancestors.

Nobody planned this. As Harari puts it, it was "a series of trivial decisions aimed mostly at filling a few stomachs and gaining a little security" that had "the cumulative effect of forcing ancient foragers to spend their days carrying water buckets under a scorching sun." Each individual choice made sense. But collectively, they locked humanity into a worse lifestyle.

And once enough people were farming and their populations grew dependent on those wheat calories, you couldn't opt out. Hunter-gatherers who stuck to the old ways would be outnumbered and pushed out by farming societies. Everyone had to join the trap or be outcompeted.

I think you can see a similar dynamic now.

The "always on" work culture is a perfect example. If 63% of young workers regularly check emails outside working hours, not checking marks you as uncommitted. If everyone stays late, leaving at 5pm signals you're not serious. But when everyone does it, we're all just working more with no competitive advantage (pure waste). German workers put in 400 fewer hours annually with identical productivity, proving the effort doesn't buy results. But American workers can't unilaterally adopt German hours without career consequences.

The teen smartphone trap shows the same structure. Each parent knows phones harm teenage mental health. The research is overwhelming. But if you're the only parent who doesn't give your child a phone, you condemn them to social exclusion. Their peers coordinate through group chats and Instagram. Individual rationality (give them a phone to avoid isolation) creates collective harm: all kids anxious, depressed, sleep-deprived. But no single family can fix it by opting out.

This is what Harari calls the "luxury trap": "One of history's few iron laws is that luxuries tend to become necessities and to spawn new obligations." Email after hours started as convenience and one upping. Now it's expected. Smartphones started as tools for emergencies. Now teenagers can't function socially without them.

Technology enables new forms of competition and comparison. Individual rational choices aggregate into collective misery. And we can't escape without coordination.

But coordination is exactly what we've lost. Weakened unions, fragmented communities, algorithmic polarization, geographic mobility. We've eroded our capacity for collective action. We're trapped in competitive races we know are destructive, but lack the institutional infrastructure to stop.

Back to doing the hard things again (please)?

So technology did deliver what it promised, and materially contributed to the foundations of a good life- it just also contributed to the things that undermine those foundations and recently, those aspects have overshadowed.

Materially, we have plenty: cheap consumer goods, more entertainment options than anyone could ever consume - drowning in what Epicurus called "natural but unnecessary" pleasures. However, the things he identified as actually necessary for a good life got squeezed from multiple directions - ironically - by tech. Healthcare and education became more expensive because of Baumol's disease. Social connection got degraded by algorithmic feeds that rewired our brains for dopamine hits instead of actual relationships and reduced our IRL time. And we got trapped in collective action problems where we can't individually escape the races we're stuck in, even when we know they're destructive.

More recently in tech investing I’ve repeatedly seen a call to arms - including the def/acc manifesto from EF to ‘do important things’ again: enough AI agents for dogs, we need to build things that actually matter. Driving this argument are frequently cited concerns over sovereignty, existential threat, and geopolitics. But it seems to me another crucial impetus is frustration: the phenomenon of seeing a bunch of hollow/performative stuff/bells and whistles and responding 'so what's the point of it/this?'

Some good news is that ‘doing hard things that matter’ is actually one of the areas I am most hopeful for the future. It seems to be having a cultural moment amongst the best and brightest. The economics of a baumol-constrained sector means even a 10% efficiency gain (vs the YC framing of a 10x better) is a huge value add and business opportunity. These spaces therefore won’t just be huge venture opportunities but actual life savers and economy savers. For the first time in history we’re mass automating judgement and unstructured work - the possibilities for critical sectors like healthcare, care, truth verification/fact-checking, scientific discovery and things that lead to the good life are enormous.

But another aspect to note implicitly is that for technological progress to lead to prosperity, it needs distribution. Technological progress itself is a necessary but not sufficient condition. And the productivity gains that happened from technological progress weren’t well distributed in the last 50 years. The technology exists for relief. The surplus exists. So where did it go? Why didn't productivity gains buy us leisure the way they used to? Inequality is at an all time high for the modern era, with wealth inequality in the West back at gilded-age, circa 1900 levels.

This question - the one of distribution- in an age of accelerating automation (which necessarily leads to an accumulation of wealth to capital holders vs labourers) will be one of the defining issues of our generation as we manage the next great transition, and I’ll talk through this in another installment.